A ChildFund peer educator leads a group discussion in Zambia about the dangers facing children in their community. Raising community awareness of child trafficking and other forms of violence against children is one way that ChildFund works to prevent it.

Danny*, 12 years old, was excited for the opportunity of his life. He had spent his entire childhood in extreme poverty, all while caring for his little brother and his mother, who had a mental disability. Some of the elders in his small town near Luangwa, Zambia, had set up a fishing job for Danny in the neighboring country of Mozambique. He would be able to continue with school there, they said, and earn good money to send back to his family.

When he arrived in Mozambique, Danny was shocked to learn that his new boss did not plan to pay him much of anything. In fact, the boss had already spent money to purchase Danny. There was no school to be found – only long hours of forced labor on the boats for little pay. Even if he could have safely escaped his boss, he didn’t know the way home. Danny had effectively been sold into slavery.

When ChildFund’s local partner organization in Luangwa noticed that Danny was missing from school, they investigated. It took several months to find Danny and get him back home, but the story had a happy ending. Many children are not so lucky.

What is child trafficking?

An estimated 27% of human trafficking victims are children. But what do we mean when we say child trafficking? We mean a form of modern slavery that can trap a child in a living nightmare for years.

Child trafficking is any exploitation of a child for the purpose of forced labor or sex. A child who is trafficked for labor might be forced to work in a sweatshop, on a farm, in a restaurant or hotel, in someone’s home as a servant, on the streets as a beggar or even in a war as a soldier. Meanwhile, a child who is trafficked for sex might be forced to work in a brothel or strip club, or for an escort or massage service. Increasingly, children who are trafficked are forced to participate in the creation of child sexual abuse images and videos that are then shared online.

What drives these heinous crimes against children, and how can we stop them? The experts have a lot to say about child trafficking around the world – and how you can play a part to end child trafficking.

Child trafficking around the world

Norman Luvera, a staffer with one of ChildFund’s local partner organizations in Zambia, says that Danny’s story is not uncommon. Child trafficking for labor is often driven by children’s own experience of poverty and their desire to live a better life.

“Most districts in Zambia, being a landlocked country, have in the past been used as transit points for children that have been trafficked from neighboring countries,” Luvera explains. “Some people that exploit young people share information on the internet about how lucrative it is to live in a foreign country, and young people find ways of moving into those countries. Most of the information which is posted on social media is taken as gospel truth by the children, especially where employment opportunities are concerned. Unfortunately, when they arrive, they are forced to engage in all sorts of illegal activities and mostly exploited.

“The saddest thing for children is that they stop school, as there are no schools in the border areas. The issue of not having proper documentation also contributes to their failing to get into school at all.”

These issues are not unique to Zambia. Similar practices trap children in modern slavery all over the world. Karamo Jatta, a staff member with one of ChildFund’s local partner organizations in The Gambia, a small country on Africa’s western coast, says that child trafficking is common in his community. “Most of the people in The Gambia do not see child trafficking as an offense, especially using the children in street begging and using them for domestic work, equally as vendors in the streets too,” says Jatta.

Meanwhile, Allan Nuñez, advocacy specialist for ChildFund Philippines, says that child trafficking around the world often goes hand in hand with sexual abuse and exploitation – and, as in many other countries, the internet plays a dark role, giving traffickers easier access to children.

The Philippines is one of the largest known sources of online exploitation of children. Estimates determine that 60,000 to 100,000 children are victims of human trafficking in the Philippines. Often, these children either go to work in child sex rings in the Philippines or are trafficked abroad as sex workers.

“In some cases, relatives use children for profit and force them to commit various sex acts in front of a webcam,” says Nuñez. “The children committing these acts are typically no older than 12 years old; in fact, the youngest victim of these crimes in the Philippines was a 2-month-old baby. Each ‘show’ can rake in about $100. In total, there were over 45,000 reports of online child sexual exploitation and abuse (OSEAC) in 2017.

“This online exploitation of children does real harm. Cybersex den operators and perpetrators have sexually assaulted, raped, tortured and beaten children,” Nuñez says. “The long-term effects of child sexual abuse can include depression, social isolation and withdrawal, feelings of anger and worthlessness, trauma, difficulty to form healthy relationships, difficulty to lead a meaningful adult life, suicide attempts and even death.”

Listening to children is an important part of protecting them from trafficking and other forms of violence. “Even before the internet boom, girls were at risk [of exploitation] at home and outside,” says Consolata, 17, in Kenya. “Now child predators can find them anywhere the moment they log in to any social site.” Consolata participates in Tuchanuke, a youth-focused ChildFund program funded by Google that works to prevent, address and respond to the online sexual exploitation and abuse of children.

Child trafficking in the U.S.

It’s tempting to think that child trafficking is a problem that only affects the developing world. On the contrary, the exploitation of children for forced labor or sex is alive and well in the United States, says Lillian Agbeyegbe, community engagement manager for the Polaris Project, a U.S.-based anti-trafficking organization. The Polaris Project operates the well-known U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline, which maintains one of the most extensive data sets on the issue of human trafficking in the United States. The hotline receives signals via phone calls, texts, online chats, emails and online tip reports.

“The data do not define the totality of human trafficking, or of a trafficking network in any given area – because not everyone has information about the trafficking hotline or the ability to make contact,” Agbeyegbe says. “We, however, have minor victims reported in all 50 states and D.C.” That includes child victims of both labor and sex trafficking.

Similar to other countries, child trafficking in the U.S. is often driven by poverty, and the most vulnerable children – such as those in our foster care system, homeless youth or those experiencing abuse or neglect at home – are the ones at greatest risk.

“Children are more vulnerable to being trafficking victims when they are in households with limited resources,” Agbeyegbe says. “Traffickers can lure them by posing to be a benefactor, offering them what is lacking in their households. Other times, children can be lured by traffickers pretending to offer a sense of connection and belonging.” She says most people are surprised to learn that young people are often trafficked by someone they know and thought they could trust – not by strangers.

Of course, the internet can dramatically blur the line of who is a stranger and who is not.

“An analysis of data collected from the trafficking hotline in 2020 showed a 22% increase in online recruitment of trafficking victims, including a 125% increase on Facebook and a 95% increase on Instagram,” Agbeyegbe says, noting that social media sites are common outlets through which traffickers lure their victims. “Children are savvy enough to be online but not mature enough to see through the deception of traffickers. Children can be more easily moved by flattery and the offers of a better life and stability that traffickers tend to offer.”

The good news, Agbeyegbe says, is that we are making progress, especially in regard to how child trafficking victims are treated.

“A common practice previously was that children who were sex trafficking victims could be arrested and prosecuted as prostitutes,” she says. “Now we have safe harbor laws practiced in a number of states and cities. The complete law protects minors from being prosecuted for prostitution and directs them to specialized services. Increasingly, more states are passing safe harbor laws or expanding their partial safe harbor laws.” Laws like these can help more young people come forward so that the criminal justice system can prosecute traffickers more effectively.

How to stop child trafficking

According to the experts, we will only stop child trafficking when all of us – governments, tech companies, nonprofits and community members themselves – work together to raise awareness of the issue, prosecute traffickers and support victims. A combination of strong laws and policies, children’s support services and community knowledge of how to prevent, recognize and report child trafficking is crucial.

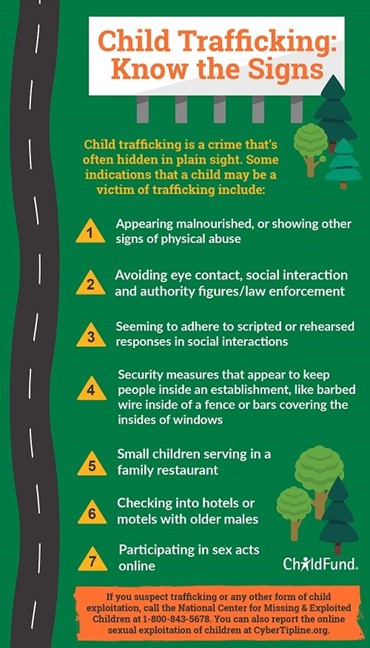

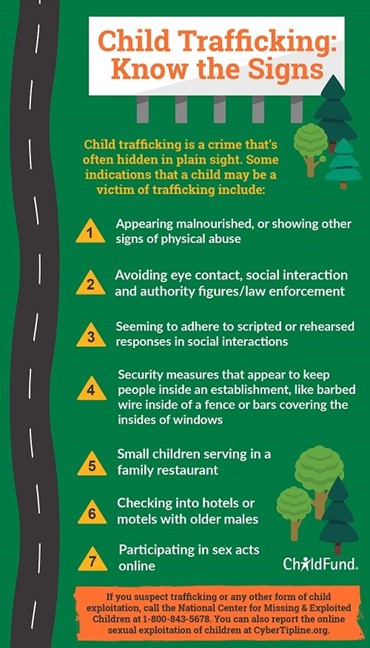

Do you know some of the signs of child trafficking?

Karamo Jatta in The Gambia, for instance, says that firm legislation to prosecute traffickers, as well as community awareness activities like the ones ChildFund operates, have reduced the number of children being shuffled around the country to engage in illegal work. “In previous years, [trafficked] children were seen rampant in the streets. This has improved due to constant sensitization and penal measures attached to the offense.

“Child trafficking is addressed as part of ChildFund’s community outreach. The organization has also contributed to policy advocacy on addressing child trafficking. And through our local partner organization, they have been supporting the Department of Social Welfare to provide for the immediate needs of children.” After all, when children’s basic needs are met, they are more protected from the levels of economic desperation that often drive child trafficking.

ChildFund’s work to help end child trafficking, exploitation and abuse is twofold: We work within communities to meet children’s needs for safety, health and education, as well as advocate at the global, national and local levels for stronger protections for children. Here, youth advocates in North Cotabato, Philippines, share messages during a World Day Against Child Labor event.

Lillian Agbeyegbe of the Polaris Project agrees that prevention is key.

“That’s why the upstream prevention work we do is very important,” she says. “We can actually prevent trafficking before it happens if we identify the vulnerable people in our communities and get to them with what they need before the trafficker does.”

Ready to take action? Here are five things you can do right now to help stop child trafficking in your own community and around the world:

- Understand what child trafficking can look like and how to report suspicious activity. You can make a report by calling the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-888-373-7888 or the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children at 1-800-843-5678. Report online exploitation of children at CyberTipline.org.

- Learn more about online sexual exploitation and abuse and its relationship to child trafficking.

- Protect the children in your life by talking to them about child trafficking, online sexual exploitation and abuse, and how they can stay safe online.

- Demand stronger protections against human trafficking from policymakers, tech companies and others who play a critical role in ending these insidious crimes.

- Donate regularly to organizations working to protect children around the world.

*Not his real name.