Site will be

unavailable for maintenance from June. 4, 11:30 p.m., to June 5, 12:30 a.m. ET. Thank you for your

patience!

The truth about child trafficking: 3 things you need to know

Posted on 07/22/2021

A young girl in India works in a rice field. Around the world, children are trafficked and forced to work for little to no pay. Photo by Jake Lyell.

We tend to think of slavery as a thing of the past. What many people don’t know is that slavery is alive and well in our world, but we call it something else: human trafficking. Here are three things you need to know about how human trafficking affects children and what you can do to help.

1. Worldwide, one-third of trafficking victims are children.

Child trafficking is the exploitation of a child for the purpose of forced labor or sex. A child who is trafficked for labor might be forced to work in a sweatshop, on a farm, in a restaurant or hotel, in someone’s home as a servant, on the streets as a beggar or even in a war as a soldier. Meanwhile, a child who is trafficked for sex might be forced to work in a brothel or strip club, or for an escort or massage service. Increasingly, children who are trafficked are forced to participate in the creation of child sexual abuse images and videos that are then shared online.

Children might be trafficked across international borders or in their home countries. Extreme poverty and armed conflict are the biggest drivers of child trafficking globally. Sometimes, a trafficker targets a child or teen when they are on their own, away from their families. Other times, children’s own families willingly allow their children to be trafficked in exchange for money or the promise of a better life. Traffickers may tell children and their families that they can help the child get a better education or a decent job. But once the child is in a trafficker’s hands, they are often held and forced to work in slave-like conditions without adequate food, shelter or education of any kind.

Sadly, once a child becomes used to these conditions, it can be very difficult for them to leave and begin a new life – even if they get the opportunity.

2. Child trafficking in the U.S. is a serious problem - but not in the way you might think.

In 2020, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children assisted law enforcement and family with more than 29,800 cases of missing children. Of those numbers, about 5 percent involved kidnappings by a family member during a custody case, 3 percent were missing young adults (ages 18-20) and 1 percent were lost or injured children. Less than 1 percent of missing children were abducted by non-family members. But the staggering majority – about 91 percent – were children who ran away from home of their own volition. Of these children, 1 in 6 likely became victims of child trafficking.

These numbers are an important reminder that most of the time, child traffickers are not strangers who jump out of the bushes and abduct children from happy homes. Rather, it is vulnerable children – those in our foster care system, or those who are experiencing abuse, neglect, poverty or hunger at home – who become easy prey for traffickers after running away. Children are most frequently abused, exploited and even trafficked by someone they know, like a relative, friend or intimate partner. And often, although exploitation is happening close to home, the child is being “sold” on the largest global market in the world: the internet.

In fact, two out of every three children sold for sex in the United States are trafficked online. That’s because technology and the internet provide many tools that traffickers can use. Online resources such as open and classified advertisement sites, adult websites, social media platforms, chatrooms and the dark web enable traffickers to interact with an increasing number of potential victims and buyers, leading to a perfect storm of opportunities for online exploitation.

Teens in ChildFund’s U.S. programs express their support for children’s right to protection from violence.

3. The online sexual exploitation and abuse of children (OSEAC) is one of the fastest-growing crimes in the world.

For these reasons and more, we can’t talk about child trafficking without talking about the online sexual exploitation and abuse of children (OSEAC). In many cases, OSEAC is a precursor to trafficking: Children are exploited by online predators, which leaves them vulnerable to being lured in by traffickers. In other cases, children who are being exploited or abused online are already trapped in a trafficking situation.

Between 1998 and 2017, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children received more than 23 million reports of child sexual abuse materials online, nearly half in 2017 alone. In 2018 alone, there were 18.4 million reports of these materials, including 45 million images and videos – more than double the number of images and videos reported in 2017. This number jumped again in 2019 and yet again in 2020, with a staggering 65.4 million videos, images and files reported.

ChildFund is working to protect children from these heinous crimes in many ways. In the Philippines, a global epicenter of OSEAC cases, we have been working for the last several years to raise awareness of the issue, most recently with a social media campaign and a webinar for parents on how to keep their children safe online. Today, the movement against OSEAC is being led by young people in the Philippines themselves. In February 2021, ChildFund also received a grant from Google to help promote online safety in Kenya and several other countries.

Meanwhile, in the Americas, ChildFund Ecuador recently designed and developed a training hub and a series of workshops for young people with information about grooming, sexting, cyberbullying, privacy and other important internet safety topics. And in the U.S., we are leading the creation of an advocacy coalition to call for improved government policy to protect children from online abuse.

An enormous global problem like OSEAC calls for all of us to join the fight against it. “When we mobilize and sensitize caregivers and community groups, including youth, to prevent and respond to online sexual exploitation,” says Chege Ngugi, ChildFund’s country director for Kenya, “when we build awareness about positive online engagement, when we promote dialogue between government and internet service providers, and when we all collaborate toward strong strategies, policies and plans to address this issue – only then – children will be much, much safer.”

In Vietnam, ChildFund’s Swipe Safe project is teaching kids how to recognize the warning signs of predators and stay safe online.

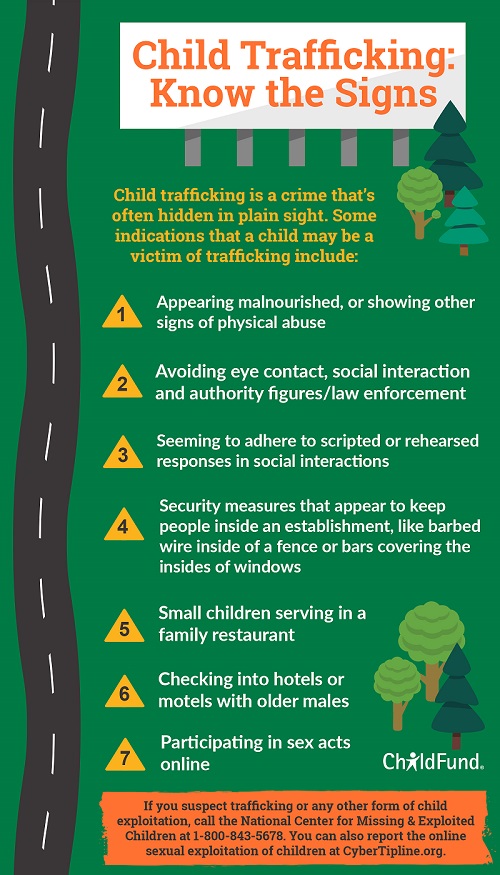

How to Help Stop Child Trafficking

The most important thing you can do to help stop child trafficking is to know the warning signs of child trafficking. It’s a crime that’s often hidden in plain sight, so pay attention to the children and teens around you, including those you may encounter online. If you suspect the production of child sexual abuse materials or any other online exploitation of children, don’t hesitate to contact the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children at CyberTipline.org or via phone at 1-800-843-5678. You can also help protect children by donating to organizations like ChildFund that are actively fighting for stronger laws against OSEAC.

If you have children of your own, talk to them about internet safety. Set boundaries for what they can and cannot do online, teach them to keep personal information private, and remind them why it’s a bad idea to talk to people they don’t know on the internet.

If we are to stop child trafficking, we all must become advocates for children’s safety and well-being. And that starts with knowing the truth about child trafficking in the U.S. and around the world. If you learned something from this article, share it: You might just teach someone else and help a child escape modern-day slavery.

Loading...